|

|

INFORMATION ABOUT JORDAN FROM KING HUSSEIN WEBSITE

Geography of Jordan

|

Jordan is a relatively small country situated at the junction of the Levantine and Arabian areas of the Middle East. The country is bordered on the north by Syria, to the east by Iraq, and by Saudi Arabia on the east and south. To the west is Israel and the occupied West Bank, while Jordan’s only outlet to the sea, the Gulf of Aqaba, is to the south. Jordan occupies an area of approximately 96,188 square kilometers including the Dead Sea, making it similar in size to Austria or Portugal. However, Jordan’s diverse terrain and landscape belie its actual size, demonstrating a variety usually found only in large countries.

Western Jordan has essentially a Mediterranean climate with a hot, dry summer, a cool, wet winter and two short transitional seasons. However, about 75% of the country can be described as having a desert climate with less than 200 mm. of rain annually. Jordan can be divided into three main geographic and climatic areas: the Jordan Valley, the Mountain Heights Plateau, and the eastern desert, or Badia region. |

|

|

|

The Jordan Valley The Jordan Valley

The Jordan Valley, which extends down the entire western flank of Jordan, is the country’s most distinctive natural feature. The Jordan Valley forms part of the Great Rift Valley of Africa, which extends down from southern Turkey through Lebanon and Syria to the salty depression of the Dead Sea, where it continues south through Aqaba and the Red Sea to eastern Africa. This fissure was created 20 million years ago by shifting tectonic plates. |

|

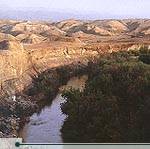

The northern segment of the Jordan Valley, known in Arabic as the Ghor, is the nation’s most fertile region. It contains the Jordan River and extends from the northern border down to the Dead Sea. The Jordan River rises from several sources, mainly the Anti-Lebanon Mountains in Syria, and flows down into Lake Tiberias (the Sea of Galilee), 212 meters below sea level. It then drains into the Dead Sea which, at 407 meters below sea level, is the lowest point on earth. The river is between 20 and 30 meters wide near its endpoint. Its flow has been much reduced and its salinity increased because significant amounts have been diverted for irrigational uses. Several degrees warmer than the rest of the country, its year-round agricultural climate, fertile soils, higher winter rainfall and extensive summer irrigation have made the Ghor the food bowl of Jordan. |

|

The Jordan River. آ© Zohrab |

|

Dead Sea at night. آ© Zohrab |

|

The Jordan River ends at the Dead Sea, which, at a level of over 407 meters below sea level, is the lowest place on the earth’s surface. It is landlocked and fed by the Jordan River and run-off from side wadis. With no outlet to the sea, intense evaporation concentrates its mineral salts and produces a hypersaline solution. The sea is saturated with salt and minerals–its salt content is about eight times higher than that of the world’s ocean–and earns its name by virtue of the fact that it supports no indigenous plant or animal life. The Dead Sea and the neighboring Zarqa Ma’een hot springs are famous for their therapeutic mineral waters, drawing visitors from all over the world. |

|

South of the Dead Sea, the Jordan Valley runs on through hot, dry Wadi ‘Araba. This spectacular valley is 155 kilometers long and is known for the sheer, barren sides of its mountains. Its primary economic contribution is through potash mining. Wadi ‘Araba rises from 300 meters below sea level at its northern end to 355 meters above sea level at Jabal Risha, and then drops down again to sea level at Aqaba. |

|

Wadi Araba. آ© Zohrab

|

|

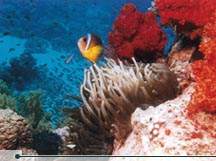

The seaside city of Aqaba is Jordan’s only outlet to the sea. Its 40 kilometer-long coastline houses not only a tourist resort and Jordan’s only port, but also some of the finest coral reefs in the world. The rich marine life of these reefs provides excellent opportunities for snorkeling and diving. |

|

The Mountain Heights Plateau The Mountain Heights Plateau

The highlands of Jordan separate the Jordan Valley and its margins from the plains of the eastern desert. This region extends the entire length of the western part of the country, and hosts most of Jordan’s main population centers, including Amman, Zarqa, Irbid and Karak. We know that ancient peoples found the area inviting as well, since one can visit the ruins of Jerash, Karak, Madaba, Petra and other historical sites which are found in the Mountain Heights Plateau. These areas receive Jordan’s highest rainfall, and are the most richly vegetated in the country. |

|

Wadi Mujib. آ© Jad Al Younis, Discovery Eco-Tourism |

|

Wadi Finan. آ© Jad Al Younis, Discovery Eco-Tourism |

|

The region, which extends from Umm Qais in the north to Ras an-Naqab in the south, is intersected by a number of valleys and riverbeds known as wadis. The Arabic word wadi means a watercourse valley which may or may not flow with water after substantial rainfall. All of the wadis which intersect this plateau, including Wadi Mujib, Wadi Mousa, Wadi Hassa and Wadi Zarqa, eventually flow into the Jordan River, the Dead Sea or the usually-dry Jordan Rift. Elevation in the highlands varies considerably, from 600 meters to about 1,500 meters above sea level, with temperature and rainfall patterns varying accordingly.

The northern part of the Mountain Heights Plateau, known as the northern highlands, extends southwards from Umm Qais to just north of Amman, and displays a typical Mediterranean climate and vegetation. This region was known historically as the Land of Gilead, and is characterized by higher elevations and cooler temperatures. |

|

South and east of the northern highlands are the northern steppes, which serve as a buffer between the highlands and the eastern desert. The area, which extends from Irbid through Mafraq and Madaba all the way south to Karak, was formerly covered in steppe vegetation. Much of this has been lost to desertification, however. In the south, the Sharra highlands extend from Shobak south to Ras an-Naqab. This high altitude plain receives little annual rainfall and is consequently lightly vegetated.

|

|

|

|

The Eastern Desert or Badia Region The Eastern Desert or Badia Region

Comprising around 75% of Jordan, this area of desert and desert steppe is part of what is known as the North Arab Desert. It stretches into Syria, Iraq and Saudi Arabia, with elevations varying between 600 and 900 meters above sea level. Climate in the Badia varies widely between day and night, and between summer and winter. Daytime summer temperatures can exceed 40آ°C, while winter nights can be very cold, dry and windy. Rainfall is minimal throughout the year, averaging less than 50 millimeters annually. Although all the regions of the Badia (or desert) are united by their harsh desert climate,similar vegetation types and sparse concentrations of population, they vary considerably according to their underlying geology. |

|

The volcanic formations of the northern Basalt Desert extend into Syria and Saudi Arabia, and are recognizable by the black basalt boulders which cover the landscape. East of the Basalt Desert, the Rweishid Desert is an undulating limestone plateau which extends to the Iraqi border. There is some grassland in this area, and some agriculture is practiced there. Northeast of Amman, the Eastern Desert is crossed by a multitude of vegetated wadis, and includes the Azraq Oasis and the Shomari Wildlife Reserve. |

|

Brightly blue lizard, Petra.

آ© Ammar Khammash |

|

To the south of Amman is the Central Desert, while Wadi Sarhan on Jordan’s eastern border drains north into Azraq. Al-Jafr Basin, south of the Central Desert, is crossed by a number of broad, sparsely-vegetated wadis. South of al-Jafr and east of the Rum Desert, al-Mudawwara Desert is characterized by isolated hills and low rocky mountains separated by broad, sandy wadis. The most famous desert in Jordan is the Rum Desert, home of the wondrous Wadi Rum landscape. Towering sandstone mesas dominate this arid area, producing one of the most fantastic desert-scapes in the world. |

|

|

|

MR ABDULLAH GHWERE

Wildlife and Vegetation

Throughout history, the land of Jordan has been renowned for its luxurious vegetation and wildlife. Ancient mosaics and stone engravings in Jawa and Wadi Qatif show pictures of oryx, Capra ibex and oxen. Known in the Bible as the “land of milk and honey,” the area was described by more recent historians and travelers as green and rich in wildlife. During the 20th century, however, the health of Jordan’s natural habitat has declined significantly. Problems such as desertification, drought and overhunting have damaged the natural landscape and will take many years to rectify.

Fortunately, Jordanians have taken great strides in recent years toward stopping and reversing the decline of their beautiful natural heritage. Even now, the Kingdom retains a rich diversity of animal and plant life that varies between the Jordan Valley, the Mountain Heights Plateau and the Badia Desert region. |

|

Arabian Oryx at the Shomari Reserve. |

|

Flora Flora

Spring is the high season for Jordanian flora, and from February to May many regions are carpeted with a dazzling array of flowering plants. More than 2000 species of plants grow in Jordan, and the variety of the country’s topography and climate is reflected in the diversity of its flora. Most of these species, however, depend heavily on the winter rains. When there is a warm, dry winter–as in 1984–many flowers either fail to appear or are considerably reduced. |

|

Anemonis in a thorny bush springtime in Jordan. آ© Ammar Khammash |

|

Jordan's national flower, the Black Iris.

|

|

Jordan boasts a wide variety of flowering wild flowers, but the most famous is the national flower -the black iris. Fields of this flower, which is not found in Europe, can be seen in masses near the town of Madaba. |

|

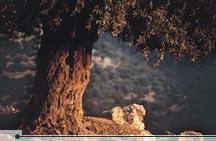

The highlands of Jordan host forests of oak and pine, as well as pistachio and cinnabar trees. Olive, eucalyptus and cedar trees thrive throughout the highlands and the Jordan Valley. Jordan’s dry climate is especially conducive to shrub trees, which require less water. Species of shrubs can be found throughout all the geographical regions of Jordan. |

|

Ancient olive trees at the village of Tibneh near Irbid, some of which could be from Roman times. آ© Ammar Khammash |

|

Flowers. آ© Zohrab

|

|

Contrary to popular conceptions, deserts are often teaming with life. Many small shrub plants thrive in the Badia, where they are often grazed by the goats of local Bedouin tribes. Several species of acacia trees can be found in the deserts, as well as a variety of sturdy wild flowers and grasses which grow among the rocks in this demanding habitat. |

|

Fauna Fauna

One can find about 70 species and subspecies of mammals, along with 73 reptile species, in Jordan. The dry climate has limited amphibian species to only four families. About 20 species of freshwater fish are found in Jordan’s rivers and streams, while around 1000 species of fish are known to exist in the rich waters of the Gulf of Aqaba. |

|

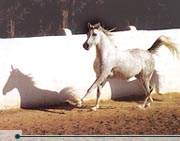

Arabian Horse |

|

Swallow- tail butterfly |

|

The harsh conditions of the desert wilderness, which covers most of the country, allow only an assortment of nature’s hardiest and most adaptable creatures to survive. As with most desert habitats, the majority of faunal life consists of insects, lizards, and small mammals. However, a number of larger mammals can be found in the desert region, including the Asiatic jackal, desert fox, striped hyena, wolf, camel, rabbit and sand rat. The white oryx, which was hunted almost to extinction, lives on the open plains, while the mountain ibex is at home among rocky, mountainous crags. Both of these two species are relatively rare. |

|

Birdlife Birdlife

Jordan also possesses a large and varied assortment of birdlife. This can be traced, once again, to the variety of habitats found within the country–from mountains forests to desert oases, from high cliffs to sweeping deserts, and from deep gorges to broad wadis. Two distinct types of avifauna can be found in Jordan: those species which stay year-round, and migratory visitors. |

|

Spur-winged Plovers in Safi. آ© Jad Al Younis, Discovery Eco-Tourism

|

|

At the junction of the Mediterranean and Arabian faunal regions, Jordan lies on one of the world’s major bird migration routes, between Africa and Eurasia. Before the water levels of the Azraq Reserve were depleted over the past ten years, up to 200,000 birds–including spoonbills, white pelicans, egrets, terns and gulls, to name a few–would congregate there at one time during the migratory season. The numbers of migrants have decreased as Azraq has grown drier, yet even today up to 220 migratory species continue to transit through Jordan on their journey north or south. The approximately 150 species which are indigenous to Jordan seem not to have been affected greatly by the great drought of the 1980s. |

|

Marine Life Marine Life

The Gulf of Aqaba is home to some of the finest marine life in the Middle East, while its coral reefs are unmatched in the world. The gulf is very narrow–at its northern end it is only five kilometers wide–and quite deep, ranging in depth from between 1000 to 1800 meters. The depth of the gulf, combined with its isolation from sea currents, minimize turbulence and improve visibility. On the sandy shores, one can find creatures such as the ghost crab, sandhoppers and the mole crab. |

|

Gulf of Aqaba |

|

The sea waters, meanwhile, host a plethora of marine life including starfish, sea cucumbers, crabs, shrimps, sea urchins, many species of fish and several worms which burrow into the sandy sea bottom. A variety of sea grasses can be found in the shallow waters, providing both food and shelter to the fishes which inhabit the area. Several species of eel make their home in the gulf’s grass beds, where one can also find sea horses and pipe fishes. |

|

Perhaps the greatest attraction for divers in the Gulf of Aqaba is the colorful coral reefs, found especially near the southern part of Jordan’s coastline. There are around 100 varieties of stony coral, and they are found mainly in shallow waters, as the algae that live within them require light for photosynthesis. Many hundreds of fish species make their homes among the reefs, and some live by eating the algae that grows on the coral. |

|

Marine meadow beneath the surface of the Gulf of Aqaba. آ© Camerapix 1994 |

|

|

|

MR . ABDULLAH GHWERE

Environmental Threats and the Jordanian Response

|

The Jordanian habitat and its wildlife communities have undergone significant changes over the centuries and continue to be threatened by a number of factors. A rapidly expanding population, industrial pollution, wildlife hunting and habitat loss due to development have taken a toll on Jordan’s wildlife population. Jordan’s absorption of hundreds of thousands of people since 1948 has resulted in the over-exploitation of many of its natural resources, and the country’s severe shortage of water has led to the draining of underwater aquifers and damage to the Azraq Oasis.

In recent decades, Jordan has addressed these and other threats to the environment, beginning the process of reversing environmental decline. A true foundation of environmental protection requires awareness upon the part of the population, and a number of governmental and non-governmental organizations are actively involved in educating the populace about environmental issues. Jordan’s Ministry of Education is also introducing new literature into the government schools’ curriculum to promote awareness of environmental issues among the young students.

The National Strategy presents specific recommendations for Jordan on a sectoral basis, addressing the areas of agriculture, air pollution, coastal and marine life, antiquities and cultural resources, mineral resources, wildlife and habitat preservation, population and settlement patterns, and water resources. The plan places considerable emphasis throughout on the conservation of water and agriculturally productive land, of which the contamination or loss of either would bring swift and significant consequences to Jordan. |

|

|

|

Wildlife Conservation Wildlife Conservation

The diversity of animals in Jordan was formerly much more varied than at present. Ancient rock drawings and Byzantine mosaics suggest that the Jordanian landscape was populated by an abundant variety of wildlife, including ostrich, gazelle, Arabian oryx, Nubian ibex, Asiatic lion, Syrian bear and Fallow deer. It is also believed that crocodiles used to inhabit the Jordan River. However, many of these species have been either decimated or driven to extinction because of overhunting or habitat destruction.

The hunting of gazelle and other wildlife dates back to the beginning of the Paleolithic era in Jordan, many thousands of years ago. However, the advent of automatic weapons and hunting from vehicles decimated the populations of larger mammals, particularly carnivores which were always present in low density. Hunting is now carefully controlled by the Royal Society for the Conservation of Nature (RSCN): laws now include the outlawing of automatic weapon hunting and shooting from vehicles. The RSCN sets the hunting seasons, the maximum quota of animals to be hunted and areas where hunting is allowed. Hunting is completely banned east of the Hijaz Railway.

The Royal Society for the Conservation of Nature has been at the forefront of Jordanian efforts for wildlife conservation. Founded in 1966, the RSCN was the first non-governmental organization of its kind in the Arab world. The Society addresses a wide range of environmental concerns, but its primary concern is for the preservation of wildlife both on the Jordanian mainland and in Aqaba’s coral reefs and coastline.

The RCSN has planned a complete system of wildlife reserves to cover the different habitats of the country. To date, six have been established, covering 1.4% of Jordan’s total area. Six more reserves are planned, and the total land area of the 12 reserves will cover four percent of the country. The Society’s preservation programs have included notable successes such as the Arabian oryx, a locally extinct species successfully reintroduced to Jordan in 1978, preservation of the remaining wetlands area at Azraq, and combining environmental preservation, archaeology and community development at the Dana Reserve. |

|

Blue-Necked Ostriches. آ© Michelle Woodward |

|

The Arabian oryx, a large straight-horned antelope which had been extinct in Jordan since the 1920s, and in the Middle East since 1972, was reintroduced in the Shomari Reserve in 1978. The breeding program has been an unqualified success. After introducing eight heads to Jordan in 1978, the Shomari Reserve now hosts around 200 Arabian oryx, together with other endangered animal species. In 1998, the RSCN plans to complete the reintroduction of the oryx by releasing them all from the Shomari Reserve into their natural desert habitat. |

|

A large number of migratory and resident birds rest at Shomari at different times throughout the year, while the park hosts a resident ostrich population on a permanent basis. The Azraq Wetland Reserve is home to around 370 species of birds, 220 of which are migrant and stop in the reserve during their annual trip between Europe and Africa. This wetlands area is rich in animal and plant life and is semi-covered by aquatic plants such as Typha and Tamarix. Wolves, red foxes, striped hyenas, Asiatic jackals and several species of insects and reptiles–including five very poisonous snakes–live in the area. |

|

Azraq Oasis (Wetland Reserve). آ© Zohrab |

|

The Wadi Mujib Reserve protects the remaining habitat of the Nubian ibex, along with ibex, Arabian gazelles, leopards, foxes, wild boars and a variety of fish and birds. Foxes and hedgehogs are some of the species protected at the Zubia Reserve, near ‘Ajloun. The roe deer was recently reintroduced to its original habitat there, and similar plans are in the works for the Persian fallow deer, a very rare species which inhabited Zubia over 110 years ago. The Dana Reserve is home to a number of endangered species including the ibex, the Arabian gazelle, and the eagle owl. A project involving the RSCN, the Noor al-Hussein Foundation and the World Bank is working to promote conservation by integrating environmental and archeological concerns with the socioeconomic development of the surrounding area. At the Wadi Rum Reserve, the RSCN is working to conserve the indigenous wildlife, including a herd of Arabian oryx and a variety of plant species–some of which are rare–as well as archeological relics and cave paintings which are over 8000 years old. In addition to these six wildlife reserves, 20 grazing reserves cover a further 20,000 hectares and provide protection against overgrazing.

While the RSCN’s immediate and tangible goals are the consolidation and expansion of Jordan’s wildlife refuge system, it also aims to increase public awareness of the importance of preserving nature. With the cooperation of the Ministry of Education, the RSCN has established over 500 nature preservation clubs in schools all over the country, with a combined membership of over 20,000 students. |

|

Deforestation and Desertification Deforestation and Desertification

Perhaps an even greater threat to Jordanian fauna and flora is the loss of habitat. Historically, Jordan used to be renowned for its forests and verdant vegetation. Numerous verses of the Bible refer to the “land of milk and honey,” yet today Jordan’s forests are much reduced in area. The main causes of deforestation have been cutting trees for wood, clearance for crop cultivation and the prevention of regeneration by overgrazing. The years 1908-17 were one of the most destructive periods for Jordanian forests, as the Ottoman Turks carried out massive felling operations to fuel their Hijaz Railway from Damascus to Madina. |

|

Deforestation has damaged the environment by decimating the habitats of many animal and plant species. Moreover, it has spurred erosion by removing the roots which keep the soil in place. With little soil stability, much of the topsoil is washed away with rain, thereby speeding desertification. In order to reverse this process, the RSCN has initiated a number of afforestation campaigns. The Jordanian Army has also served by planting trees on barren government land in Irbid, Salt, Mafraq, ‘Ajloun and Karak. |

|

Protecting Aqaba Protecting Aqaba

The Gulf of Aqaba, a branch of the Red Sea with 367 kilometers of coastline, 27 of which belong to Jordan, is one of the Kingdom’s primary tourist attractions and its only port access. Fortunately, however, Aqaba has always been acknowledged as more than a center of trade and tourism. Boasting one of the world’s most unique coral reef systems and rich in fish and aquatic plant life, the Gulf of Aqaba is an environmental treasure which Jordan is endeavoring to protect. |

|

Aqaba. آ© Zohrab |

|

The enclosed nature of this marine environment, which encourages its unique biological diversity, also makes it particularly susceptible to pollution from trade, industry and tourism. The existing and potential environmental threats to Aqaba include such industrial pollution as that from phosphates, potash, cement, traffic, electricity generation and shipping. Tourism contributes to individual littering, garbage accumulation, and increases in sewage problems, air pollution and traffic levels. As Aqaba is a major tourism center and the country’s only port, plans for preserving this natural treasure have necessarily been combined with the region’s economic and social development. Jordan’s early commitment to sustainable development has facilitated this combination, as environmental regulation has been instituted relatively early in the industrialization process.

The Aqaba Regional Authority (ARA), established in 1984, is a specialized governing body responsible for the social and economic development of the Aqaba region. The ARA is responsible for monitoring and controlling all major construction activities along the coast. Future industrial development of the area, while encouraged, is controlled by a strict set of requirements. In recent years, the ARA has taken the lead by establishing the Aqaba Marine Reserve. Another function served by the ARA is that of environmental monitoring. In October 1989, in conjunction with the Royal Scientific Society, the ARA began regular monitoring of drinking water, seawater, treated wastewater and cooling water from selected coastal facilities.

Another of Jordan’s conservation efforts in the Aqaba area is the Aqaba Marine Science Station, established in 1982. The station is the working center for the study and preservation of Aqaba’s marine life. Scientists from the University of Jordan and Yarmouk University are actively engaged here in marine ecology and oceanographic research.

While Jordan is actively engaged at the national level to preserve Aqaba’s environment, the fact that four countries–Jordan, Egypt, Israel and Saudi Arabia–share coastline around the Gulf of Aqaba means that any long-term planning for preservation of this unique and fragile marine ecosystem must be done on a regional basis.

Throughout the Gulf of Aqaba region, industrial and economic growth is being actively stimulated. Therefore, environmental protection must be combined with growth in a comprehensive sustainable development plan. The Gulf of Aqaba Environmental Action Plan (GAEAP) was established by the multilateral working group on the environment to curb existing damage and prevent future harm by establishing a regulatory framework and coordinating policies among the various governmental ministries associated with environmental protection. The plan calls for an environmental audit of Jordan’s nearby power plant, updated contingency plans for oil spills, improved monitoring of air and marine water quality and the management of the protected marine area. The primary benefit of the GAEAP will be the local capability to contain the undesirable consequences of development by preserving the marine and desert environments, reducing pollutants and establishing water use efficiency measures.

The strategy proposed by GAEAP is complemented by two existing projects: the Egypt Red Sea Coastal Zone Management project and the Yemen Marine Ecosystem Protection project. It is hoped that a comprehensive environmental accord will be negotiated soon between the four Gulf of Aqaba states, establishing a long-term regional framework for pollution control. |

|

The peace treaty signed by Jordan and Israel in October 1994 gave special attention to arrangements for the Aqaba/Eilat region, and the two countries recently signed a protocol outlining a detailed framework for cooperation in conserving this delicate ecosystem. Special attention was given to the dangers of industrial pollution from shipping. Moreover, the protocol stipulated the establishment of a jointly-run Red Sea Marine Peace Park to ensure protection of the coral reefs and marine environment from abuse and overuse. |

|

The National Environmental Strategy The National Environmental Strategy

For Jordan, environmentalism is neither a luxury nor a trend destined to go out of style in time. The country’s scarce resources and fragile ecosystems necessitate a viable and ongoing program of action covering all aspects of environmental protection. In order to maintain a viable resource base for economic growth, as well as to preserve the region’s natural heritage, Jordan became the first country in the Middle East to adopt a national environmental strategy. With help from the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), in May 1992 a team of over 180 Jordanian specialists completed a practical and comprehensive working document entitled National Environment Strategy for Jordan.

The document is a long-term environmental blueprint for government, NGOs, private sector businesses, communities and individuals. It also contains a wealth of information about Jordan’s natural and socio-economic environment. The strategy is predicated on the fundamental principle of sustainable development, which the report defines as “development which increasingly meets human needs, without depleting the matter and energy of the ecosystem upon which development is founded. An economy which develops sustainably would be designed to perform at a level which would allow the underlying ecosystem to function and renew itself ceaselessly.”

The document offers over 400 specific recommendations concerning a wide variety of environmental and developmental issues. Moreover, the plan outlines five strategic initiatives for facilitating and institutionalizing long-term progress in the environmental sphere:

(1) Construction of a comprehensive legal framework for environmental management

(2) Across-the-board strengthening of existing environmental institutions and agencies, particularly the Department of Environment and the RSCN

(3) Giving an expanded role for Jordan’s protected areas

(4) Promotion of public awareness of and participation in environmental protection programs

(5) Giving sectoral priority to water conservation and slowing Jordan’s rapid population growth |

|

|

JORDAN FOR EVER

|

|